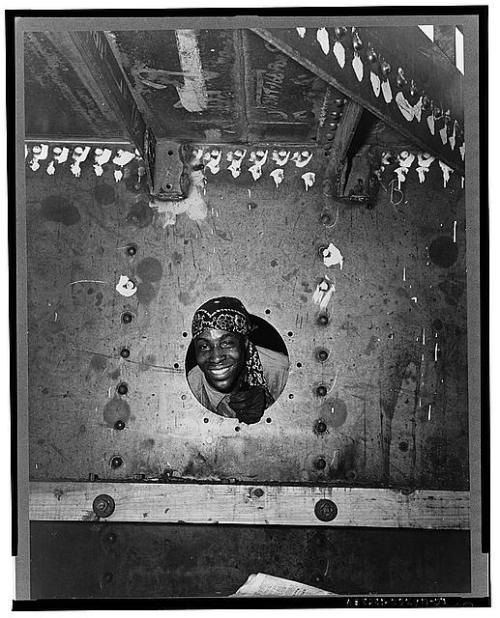

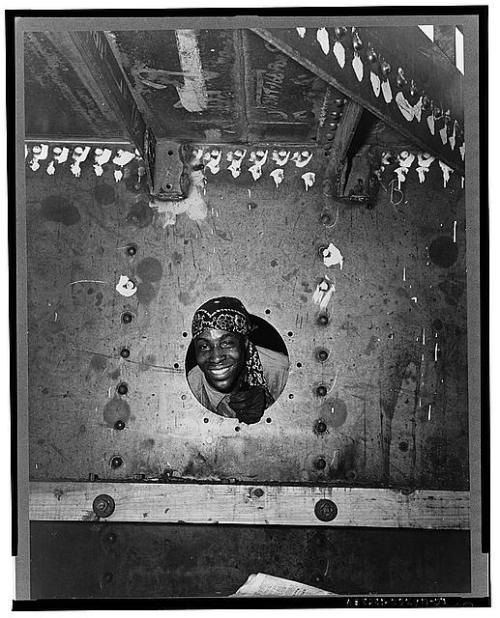

Building the SS Frederick Douglass. Smiling from the porthole is rivet heater Willie Smith. (Photograph by Roger Smith, Office of War Information, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

[Weekly Writing Challenge: Truth is Stranger than Fiction

“For this challenge, we want to see a photo of someone looking truly happy. . . Then we want to know why: what’s going on in the photo? . . . We’re sure you could invent Hollywood mega-hit-worthy explanations for your subject’s happiness . . . but this week, we’d rather know what’s real.”]

This year’s best picture nominees, and ultimately the winner of that award, took on some big topics in American history: U.S. involvement overseas (Argo and Zero Dark Thirty) and slavery (Lincoln and Django Unchained). To varying degrees, each of these four films dealt in the truth but made it into movies their makers called fiction. Argo underplayed the Canadians and made up some drama. Torture didn’t quite work out the way ZDT played it. Django seemed almost purely fantastical but check out the true story of Dangerfield Newby and think again. And Lincoln? Lincoln left out Douglass making the movie a little narrower than it ought to have been.

In truth, Frederick Douglass looms too large to be left out. In this photo taken by Roger Smith for the Office of War Information, we see a worker identified as Willie Smith. Smith smiles delightedly out of a porthole in the dock house of a ship named after Douglass. The time is May, 1943. The location is the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyard in Baltimore, Maryland. The photograph’s original caption informs us that this shipyard is roughly where Douglass, while still a slave in the 1830s, was sent to work by his master to earn extra money working as a caulker. Douglass recounts in his Narrative that as a child of twelve, he had learned to write partly by watching ship’s carpenters at the Baltimore yards mark boards with letters for different sides of the ship. Later, when Douglass returned to Baltimore as a young man (after having had a knock-down, drag out fight with a slave breaker who ended up being the one broken), he was apprenticed out to the shipyard. He was there for months until one day the white apprentice carpenters started objecting to working with black men and set upon him. Tarantino might take note of Douglass’s description of the fight:

“[They] came upon me, armed with sticks, stones, and heavy handspikes. One came in front with a half brick. There was one at each side of me, and one behind me. While I was attending to those in front, and on either side, the one behind ran up with the handspike, and struck me a heavy blow upon the head. It stunned me. I fell, and with this they all ran upon me, and fell to beating me with their fists. I let them lay on for a while, gathering strength. In an instant, I gave a sudden surge, and rose to my hands and knees. Just as I did that, one of their number gave me, with his heavy boot, a powerful kick in the left eye. My eyeball seemed to have burst. When they saw my eye closed, and badly swollen, they left me. With this I seized the handspike, and for a time pursued them. But here the carpenters interfered, and I thought I might as well give it up. It was impossible to stand my hand against so many. . .”

Although Douglass couldn’t return to work there, his master later sent him out to another yard where he learned to caulk the hulls of ships. When he finally escaped to freedom in Massachusetts, he tried to get similar work in the shipyards of Nantucket, only to find that the white workers there also excluded free black men from such skilled professions. (Back in Baltimore, free black workers formed a Caulkers Union in 1838 and used it to insist on being paid fair wages. They succeeded until 1865,when white workers went on strike to force the shipyard owners to fire the black men.)

If we fast forward to the time of the photograph of riveter Willie Smith, we can start to understand some of the reasons for his joy. Slavery, of course, had long since ended, due in no small part to the leadership of individuals like Douglass. Job discrimination persisted, however, even as the nation mobilized in support of a war against fascism. Only the threat of a full scale march on Washington by A. Philip Randolph in 1941 finally convinced President Franklin Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802 that prohibited discrimination based on race, creed, color, or national origin in the defense industries. But black workers still faced segregation both in the military and on the home front. Workers at the Bethlehem Fairfield Shipyards remained segregated through the end of the war. Another photograph from the Office of War Information attests to how far this went:

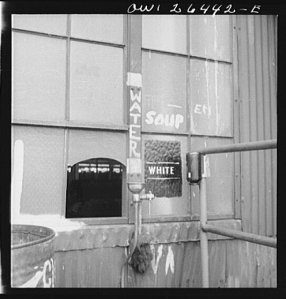

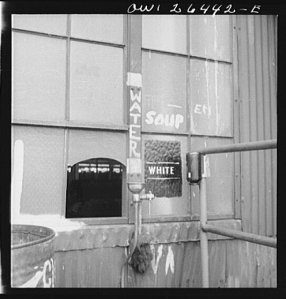

A Drinking Fountain, Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards (Photo by Arthur Siegel, Office of War Information, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Yep, white only drinking fountains for workers building ships for the United States government in Maryland–hardly the deep South.

Still Willie Smith smiles. We might take a minute to consider who he’s smiling at. The photographer is Roger Smith, probably no relation to Willie. Roger Smith worked for the Negro News Division of the Office of War Information. Although a prolific photographer who extensively documented African American participation in the war effort, he remains very little known. The single best measure of this is probably the fact that of the twelve Roger Smiths listed on Wikipedia, as of this writing he is not one of them. What is known is that his work was marginalized and that as a black photographer, he mostly got assigned to photograph black subjects.

He did so brilliantly. He is especially notable for having photographed the country’s first black Marines.

“… Although a dress uniform is not a part of the regular equipment, most of the Negro Marines spend $54 out of their pay for what is generally considered the snappiest uniform in the armed services… Photo shows a group of the Negro volunteers in their dress uniforms.” Ca. May 1943. Roger Smith. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

These men are not smiling, but surely that was because this formal photograph was intended to show their seriousness of purpose. It might also have been because their battles still lay ahead. The Marines were the last branch of the United States military to allow African Americans to enlist, and until 1949, they were housed at a segregated camp called Montford Point. In 2012, the surviving members of the group (known informally as the Montford Point Marines) were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the country’s highest civilian honor, in recognition of the discrimination they had faced—including having been excluded from combat roles. However overdue, Frederick Douglass might have smiled. At the start of Lincoln, the black soldiers who we see fighting in the film’s only combat sequence took part in the Civil War thanks in large measure to Douglass’s relentless advocacy to the Lincoln administration. This didn’t make it into the film, but it happened.

And so Willie Smith, who played the smallest of parts in the largest of wars, smiles, too. He knows what his photograph means.

(Postscript: The ship Smith helped to build, the SS Frederick Douglass, was a freighter. Perhaps this is unsurprising given that African American soldiers were generally assigned to support roles rather than combat during World Wars I and II. The ship and its mixed race crew was under the command of Captain Adrian Richardson, only the second black man appointed to such a position during the war. A German U-boat sank the Douglass on September 20, 1943 as part of a larger assault on the New York bound convoy of U.S. warships. A British ship rescued the Douglass’s entire crew, plus “one female stowaway.” This is also a true story.)